What you read into this photograph will depend almost as much on you as on what these actors are doing. Our response to people, actors included, is always subjective. Clearly some intimacy is being shared here; he is invading her space. There is something invidious about the way he seems to be caressing her cheek with his hand. She, on the other hand shows no urge to pull away, and her downcast look seems doomed. She has given in, or given up. There is little expression in their faces, but these are good actors, and there is a charge of sexual tension in their relationship.

Actors have a range of tools at their disposal. They can use their voice and facial expression, their eyes and movement. They have a subtle control of timing. They can strike the right pose. They have charisma, sex appeal, “chemistry”. In animation you have the actor’s voice, of course, but everything else has to be created synthetically. Everything else is an illusion. Every semblance of sex appeal, timing, and posing is the creation of a director, animator, layout artist, and the writer.

Good film writing is about showing, not telling, and this is especially true of animation. Over the next few weeks I’m going to be talking about some of the things a writer can put into the script to show what the characters are feeling.

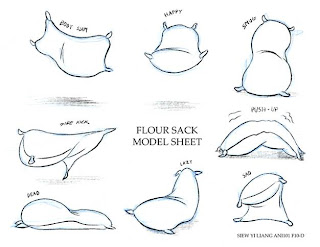

Perhaps the most important part of any animation is the posing. You can give virtually anything expression by posing it in the right way. Here is a model sheet of a flour sack.

This sack can be brought to life and given expression through the way it is posed, from its place in the composition of the shot, and, of course, the way it moves. In itself it has no charisma or sex appeal. You can’t look into its eyes and see the depth of its soul. You can even give a drawing expression with its line. There is a great difference between a character drawn with a wispy, fragile line, and one drawn thick and bold!

Of course, you don’t have to write every pose for every character, but I think it is a good exercise for animation writers to imagine their characters are flour sacks, and need to be given clear, visual indication of how they move and what they are doing.

I started my career as an actor, and, like most actors, spent a lot of time observing myself and others to pick up little gestures and movements that give people expression. Actors like to work with props, and should be able to use a cigarette, a glass, or a pencil in various different ways to project different states of mind. Having studied at the Laban art of movement centre, I was particularly interested in how people moved. One of the first things that happens in the design of animated characters in whatever medium is a walk cycle, because this will be the most important element in the definition of character.

In my classes, I get my budding writers to come up with little gestural motifs, with and without props, that express different states of minds: nervousness, aggression, or delight. Then I make them write them down.

Thomas stands in the corner twiddling his thumbs, however, is probably never going to appear in an animated script. In an animated script, you are more likely to find Thomas stands in the corner tying a large knot in his tail. The usual rule with animation is: If it can be done in live action, do it in live action. Animation is about fantasy, and that’s where the fun bit comes in.

Next: Things that actors can’t do.

The next part of this blog will appear in the first week in January. Merry Christmas, everyone!

No comments:

Post a Comment